The value of fractal geometry for primary children

An important part of NUSTEM’s role is supporting academics in Northumbria University to translate and communicate their research to new audiences. We first worked with Northumbria University’s maths academic Matteo Sommacal during the sixth-form evening lecture, where he fascinated year 11 and 12 students with the complex beauty of fractal geometry.

In the summer term of 2024 we worked with Matteo again, this time to develop the ‘The Mathematician’, a classroom workshop about fractal geometry for primary school children in Year 5 and 6. The classroom workshop aimed to provide a real-world enrichment experience and showcase an alternative side of maths than children experience through national curriculum topics.

Maths is a rich tapestry, yet there is only scope within the national curriculum to include a small sub-set of the possible areas of mathematical exploration. Fractal geometry is a vibrant and important area of mathematics. Studying fractal geometry is looking for the formula in the complex and irregular. Nature can provide us many examples (clouds, snowflakes, cauliflowers, coastlines, trees), all of which have self-similar patterns. Look closely at a fractal and you will see that the complexity is still present at a smaller scale. While it can be appreciated just for its beauty, fractal geometry also presents a different way of seeing the world. It provides mathematicians with a way to understand the complexity in systems as well as shapes.

Besides his passion for fractal geometry, one of Matteo’s motivations to work with NUSTEM is that when young people came to study Maths at University they could be initially confused when they first encounter different branches of maths they hadn’t known existed. The Mathematician aims to show children that maths isn’t just numbers and equations, it can also be about pattern and repetition.

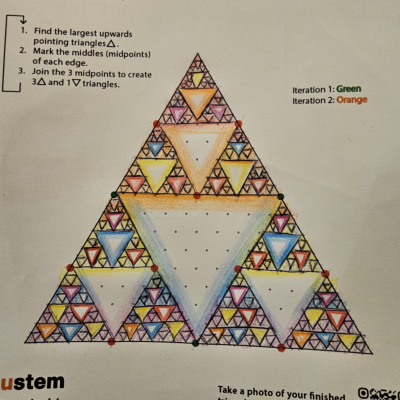

In the developed workshop children are introduced to self-similar patterns and were asked to explore them in images of nature. They learn why mathematicians struggle to measure the perimeter of the UK coastline and how fractal geometry can be useful in addressing this challenge. Lastly, children look at how the Sierpinski triangle is formed through a specific algorithm, and draw their own Sierpinski triangles, which are showcased here.

The workshop was evaluated firstly using reflexive practice among delivery staff to refine the delivery in the formative stages, and then using a using a pre- and post- workshop evaluation worksheet for pupils. Pupils were asked to describe the first three words that come to mind when they think about maths, and their feelings about the workshop. Post-workshop feedback was also collected from teachers.

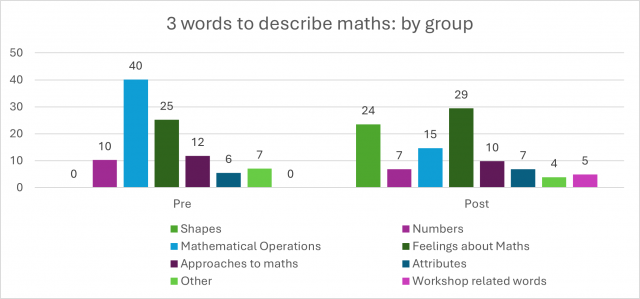

In the pre-workshop evaluation, we found that 40% of the children describe maths by its mathematical operations (addition, subtraction, division and multiplication, or branches of maths (geometry, algebra), with 10% describing maths to be about numbers. 12% of pupils saw maths as an approach, such as learning (6%) and problem solving (4%). Only one child described maths as being about identifying patterns (1%). 25% of children described maths through feelings or emotion, of these 38% described maths as hard, 38% as exciting, 13% as interesting and 13% as easy. Before the workshop children mostly said they felt good or excited. A couple of children said they felt nervous, one saying they were bad and maths, and another saying it would be better than the alternatives, “Better than writing isn’t it?”.

In pupils’ post workshop evaluation responses, we saw 24% of children describing maths by shape, and a reduction in the percentage of children describing maths by its operations (pre: 40%, post 15%). In approaches to maths, children now describe maths as being about pattern, reflecting the content about recognising self-similar patterns, and much less about problem-solving or gathering knowledge. More children described maths by feelings, with an increase of 35% in children describing it as fun/like it, and a reduction of 18% of children describing maths as hard.

The evaluation found that the workshop achieved its intended aim. Children described feeling calm and creative in the workshop and thinking that maths is ‘beautiful’. One year 6 child said, “the coastline problem was ‘intriguing’ and gave me a new way of looking at the world.” Teachers’ feedback affirmed that the workshop had supported children to see maths in a new light. One teacher said, “Maths is more than integers and the 4 operations”. The appeal of the workshop in engaging different audiences with maths was also praised by one teacher,

“I feel that maths in Y6 can sometimes be ‘functional’ but your session was inspiring. The children really enjoyed thinking about a different aspect of maths and it was striking that there were five or six children who can struggle with calculation, who embraced how maths was presented today. I felt that the children gained so much from this exercise. All of them were able to achieve and this is a huge confidence-boost for those who often assume that they aren’t ‘good at maths’.”

Year 6 Teacher

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!