What is Science Capital?

NUSTEM is working in the North East of England to increase levels of science capital in children and their support networks. But what does this actually mean, and how are we going about it?

Science Capital: An Introduction

As defined by the ASPIRES project:

“Science capital refers to science-related qualifications, understanding, knowledge (about science and ‘how it works’), interest and social contacts (e.g. knowing someone who works in a science-related job).” (ASPIRES, 2013)

The video above describes science capital like a giant “holdall” containing pupils’ knowledge, attitudes, skills and experience, which they carry around with them and use to negotiate life and to make decisions.

Science capital can be broken down into four elements:

- what you know

- how you think

- what you do

- who you know

Science Capital: A Definition

Science capital is a recently established term developed to apply the concepts of social capital and cultural capital within a scientific context. The foundation work builds on that of Pierre Bourdieu.

Social capital is the idea that our social networks – the people we know and interact with and our status in social groups – have value. Being part of a social group is valuable to us as it allows us to achieve things that we couldn’t on our own. A good example of social capital in action is a neighbourhood watch scheme. However if you are not connected to a social group then you cannot gain the value that comes from being part of that group, and so Bourdieu argues that social capital can produce or reproduce inequalities in society.

Cultural capital is the idea that the forms of knowledge and skills that people acquire by being part of a particular social class (skills, tastes, mannerisms, clothing etc) have value. Cultural capital is valuable to us when we interact with people with similar cultural capital as ourselves – someone with the same taste in music or who went to the same school, say – as it creates a sense of collective identity and group position, of “people like us”. However because certain forms of cultural capital are valued above others in society, if you do not have these forms of cultural capital it can work to reduce your social mobility by reproducing existing inequalities in society.

As with social and cultural capital, ASPIRES found that science capital can also reproduce inequalities in society. They found that pupils with higher levels of science capital in their family were more likely to aspire towards a science-related career, and that pupils with lower levels of science capital were less likely to aspire to a science-related career.

How does NUSTEM hope to build science capital in the region?

NUSTEM is working with over 30 partner schools in the North East of England, offering curriculum enrichment, interactive out-of-school workshops and support and training for teachers. We also work directly with local communities, and through partner organisations including local councils.

We believe that levels of science capital can be increased by:

Engaging parents

•Involving parents in children’s science education. This could be via collaborative homework or initiatives that work with parents directly such as Science for Families.

•Letting parents know its OK not to know the answers to everything children ask about science, and promoting “I don’t know, let’s see if we can find out”.

•Making sure parents are aware of the wide range of career options with science – whether at school Options and Choices evenings, or through the provision of unbiased careers information.

Revealing the relevance of science

•Exploring how a particular area of the STEM curriculum is relevant to real life.

•Highlighting the different careers that are related to topics taught in school.

Challenging popular stereotypes

•Presenting STEM as ‘normal,’ not ‘hard’.

•Challenging gendered attitudes around appropriate career choices for boys and girls.

Being aware of language

•Introducing the variety of science-related jobs from an early age. For example, our Key Stage 1 and 2 workshops cast children in the role of ’structural engineer’ or ‘botanist,’ and build their understanding of subject, context, and career possibilities.

•Highlighting that the English language is inherently gendered, and the role this can play in defining children’s norms and identities.

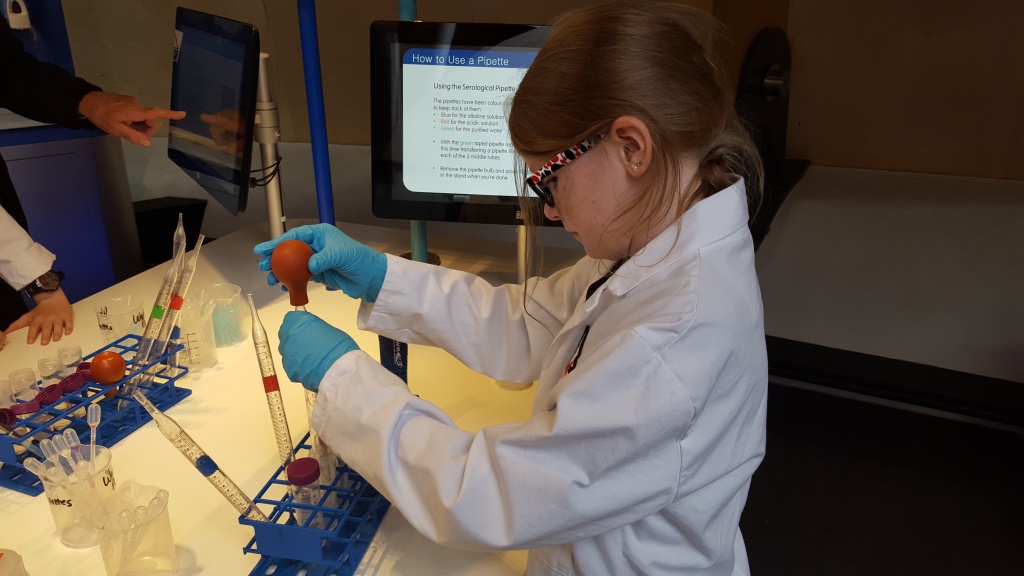

Creating different opportunities for children to explore STEM

•Providing opportunities for children to explore STEM at museums, galleries and science centres.

•Increasing contact with people who work in STEM jobs by bringing them into classroom to talk about their work. This might include parents.

NUSTEM’s direct interactions with children and families seek to reinforce these key messages. We also support teachers to share these messages within their teaching, by providing training and additional resources on key topics.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

This is what we at CASTME are trying to promote in the Commonwealth see http://commonwealtheducation.org/members/