Mini Mangonel

Tinkering & flinging mechanism

Jonathan Sanderson

NUSTEM, July 2021

Jonathan Sanderson

NUSTEM, July 2021

A simple catapult design that’s as easy to make as possible, uses cheap materials, and lends itself to exploratory improvement. Great as an end-of-term activity for a class, at home on a rainy afternoon, or for big drop-in events.

We’ve written previously about ‘tinkering’: exploring mechanisms and engineering through experimental play. The idea isn’t new, but thinking about the value of tinkering in both formal and informal learning settings has been spearheaded recently by The Tinkering Studio at the Exploratorium in San Francisco. They’ve done some fabulous work over the years, which has been highly influential in visitor centre circles – not least here in Newcastle, where both the Discovery Museum’s Play+Invent Space and Life Science Centre’s Maker Studio have very much drawn on the ethos of tinkering.

There are many descriptions of what tinkering entails; mine goes like this:

Central to this is that in tinkering activities, the participant fully expects to fail. As educators we often talk about ‘learning through mistakes,’ but it’s hard to achieve in practice: in most situations when you’re making something, failing to reach your intended destination is frustrating. If you’re genuinely exploring, however, an interesting failure might point you in a new direction.

It’s very common for tinkering play to prompt a solid idea, and to transition seamlessly into making: “If I put this together like this, I could… ooh, I could make one of these!”

What’s much less common is going from a making activity back to tinkering. Which is what we set out to do with these catapults.

The truth is, I’m not completely convinced my understanding of siege engine terminology is correct. But I’m reasonably certain that the type of mechanism employed here is a ‘traction trebuchet‘ or ‘mangonel.’ It isn’t an onager, springald or ballista.

Catapults – I think – are the generic class of device: all the weird and wonderful pieces of engineering named above are types of catapults. Except maybe the ballista.

Further down the page you’ll find a handy A4 page you can print off which has all the detail you need – we’ve done this activity with many hundreds of people and found this set of pictures adequate.

Are they perfectly clear? No. But that’s sort-of the point. The mechanism is simple enough that most people can puzzle their way through. They might make a few mistakes along the way, but they’ll observe other people’s constructions and work out what they’ve done wrong. That practical experience of trial-and-error is what this activity is all about, so while we did at one point make some clearer instructions… we threw them away again, and went back to these.

Tape the square of card to the base of the cup.

You also need to fix the spoon to the other piece of card. We like glue guns for this, but tape will do if necessary. There are many ways of getting this wrong, which you may or may not find out.

This is the fiddly bit. At the end of it, you should have a flappy masking tape hinge with the card and spoon moving freely. This… may not happen the first time you try.

Stand the cup up, and slip the elastic band around the cup and spoon.

Done! (…for now)

You can launch anything light – wadded up newspaper works well, as do those little fluffy chicks you can get at Easter. But our preference is a standard table tennis ball:

The tricky part is keeping the ball balanced while you pull the spoon back. Our preferred technique is to hold the spoon horizontal and tip the cup forwards, but we’ve found some people’s sense of what’s right and proper with catapults is offended by that. So try a few things out and see what works for you.

With a little practice, you should find that your ball flies in a nice arc and lands up to about a metre away. Success!

For some people, this is achievement in itself: in the space of a few minutes they’ve made a delightful little mechanism which works. Maybe they’ve fiddled with the hinge to get it to move right, or they stuck the wrong bit down, worked out what they’d done, and had to start again. Great. Well done.

But…

Modify your catapult to launch a table tennis ball as far as you can. Rules:

The ‘one loop of elastic’ rule is there for several reasons. Firstly, it’s where the challenge comes in: if you load up a zillion elastic bands you can fling a ping-pong ball basically as far as you like. Too easy. Also, it’s a safety issue: you want to be absolutely sure that the elastic band will break (twanged knuckles: ouch, but you’ll recover) rather than the teaspoon (shards of sharp plastic flying in all directions).

When we’re running this at a large-scale event, we’ll try to arrange a firing range of at least 9 metres. Yes, really.

We don’t want to say too much here, because the whole point is to explore for yourself and figure things out. But we prompt groups with questions like:

Spoiler (click to reveal)

The choice of tapered paper cups and the setup of the spoon/hinge is very deliberate: the elastic band rolls down the taper, which reduces both the band tension and the distance of the point of application of force from the hinge. Very few children spot this themselves, but almost everyone will subconsciously roll the elastic band back up the cup after launching. Astonishingly, most people’s intuition here is better than their cognition: they’ll be telling the facilitator they ‘can’t think what to do’ to improve their catapult even while their hands are solving the most glaring problem for them.

Coaching a group to spot this for themselves is one of the great joys of running the activity.

We’ve tried enough different elastic bands and table tennis balls that our results aren’t strictly comparable between sessions. But for reference:

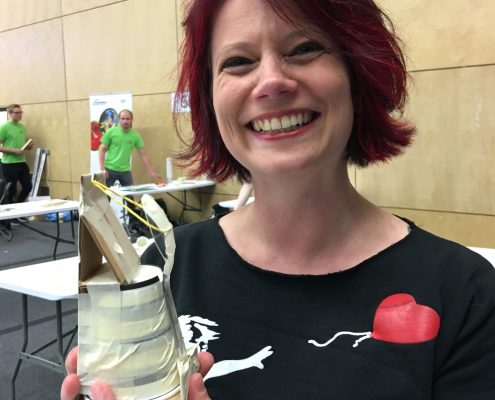

To give you some idea, here’s Dr. Emma King of the Royal Institution with her design, which achieved 8.74m in June 2016.

To give you some idea, here’s Dr. Emma King of the Royal Institution with her design, which achieved 8.74m in June 2016.

Emma’s degree is in astronautics (space engineering), which may constitute cheating.

While we have used this activity in school settings, we’ve more commonly used it for big drop-in events, like careers fairs and open days.

We’ve typically set up a glue-gun station which we can keep a close eye on, and several working tables with stocks of cardboard, scissors and masking tape. It’s good to have groups of people working alongside each other – often, they’ll iterate on each others’ designs collaboratively.

Separate from the work tables we’ve then had a long set of trestle tables as a ‘firing range’, with a tape measure stretched out, marks at 1m intervals, and a very clear start point. If your room has a high ceiling you’ll need 8 or so metres of tables (!).

We’ll only count balls which land on the firing range, and it’s really important that whoever’s staffing it shouts the distance clearly before anyone else can exaggerate it. We’ve sometimes had a leaderboard (cardboard strips, a sharpy, map pins, and a poster board).

At drop-in events like open days, we’ve set up working areas for about 30 participants at once (coming and going constantly), and three staff have been able to manage that reasonably well. A fourth is helpful. People might spend just a few minutes making the basic catapult, or they might dwell for several hours (!) honing their design, trying something different, experimenting, and determined to improve.

School classrooms can work, but you often have to launch on the floor to eek out that extra bit of ceiling height. If you’re like us, this is problematic for knees. Chasing ping-pong balls is particularly awkward.

The biggest challenge we’ve had has been some facilitators thinking of the activity as a ‘make and take’, and literally packing children off as soon as they’ve made a working catapult. Sometimes this is about capacity – if there are thousands of people at an event, you can argue it’s better to spread the activity thinly across more of them. But at other times it’s been a missed opportunity. In many ways this is a training issue, but we’ve found that ‘the tinkering mindset’ is sometimes hard to convey. More experienced facilitators and teachers are sometimes so well-versed in coaxing ‘success’ out of their students that they struggle instead to prompt for observation, ‘what if’ conceptualisation, and experimentation.

The biggest challenges in a school setting would be about the physical space: you really want a high ceiling, a long firing range, and plenty of standing-height table working areas. We’ve run it in a standard classroom with parent/child groups and it’s worked well enough, but a hall would be better.

Do make sure you’ve made a working catapult yourself. It helps to have a few working examples to show around, so participants can compare theirs with a functional example. But mostly, you need to check you have a combination of components that works. Problems can include:

You’re very welcome to download this instruction sheet, print it off, and use it for your own activities. Almost nobody ever reads the text, but they seem to do well enough from the pictures.

Our friend Alom Shaha has a new book (July 2021) called Mr. Shaha’s Marvellous Machines. It’s full of mechanisms you can make using materials you genuinely have lying around at home, including a version of this mangonel.

In this film he show us his version. Fame at last!

Make a wormery

Make a wormery

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!