What is an environmental scientist?

Environmental scientists study the environment, and particularly the effects of human activity on it. By conducting tests and analysing data, they try to work out how to prevent and solve environmental problems.

They’ll gather samples and observational data in the field, and conduct tests in the lab. They analyse soil or air samples to find the type, concentration and source of pollution, which might be caused by industry or agriculture. The environmental scientist will identify whether the contamination could harm wildlife, plants or people. They’ll then identify ways to manage, minimise or eliminate negative impacts of the pollution.

Attributes: passionate, creative, committed

Chromatography

How does chromatography work?

Chromatography is a way of separating out a mixture into its different parts. We see objects because they reflect light into our eyes. Some molecules only reflect particular colours; when that light reaches our eyes, we see the object it reflected off as being a particular colour.

You’re probably used to the idea of ‘primary’ colours – colours which can be mixed together to make other colours. You’ve maybe mixed red, yellow and blue paints in different combinations to make greens, purples and oranges. The dyes in felt-tip pens might look like a single colour (‘dark blue’ or ‘light green’), but to achieve those colours a scientist might have mixed several pigments together.

Liquid chromatography – in the case of felt-tips, dabbing some dye on the end of a piece of tissue paper, then letting water soak up the paper, carrying the dye with it – can let you discover the hidden colours in the pen dyes. The solvent (water) is absorbed up the paper, taking the mixture with it. But larger, heavier molecules are dragged along more slowly than smaller, lighter ones, so the blob of dye gets spread out. Different parts of the smeared-out dye will be made of different pigments, which you’ll see as different colours.

Add all those colours up and you get the colour of the pen you started with.

How do environmental scientists use chromatography?

The paper chromatography you can do with felt-tip pens looks pretty, but it turns out not to be terribly useful for working scientists. However, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is the same idea, and it’s used very widely in chemistry. Just like paper chromatography, you use water (or another liquid) as a solvent to separate the components of the material you’re trying to investigate, like a dye. Rather than using tissue paper, you let the liquid flow along a ‘column’ – a thin tube – which is perhaps 10 or 20 cm long. You then investigate the substances which emerge from the end of the column, and how they change over time.

So with pen dye, the smaller pigment molecules would emerge first, with the larger ones making their way out later. Chemists, including environmental scientists, can use HPLC to investigate a wide range of samples.

Gas Chromatography is similar, but the solvent isn’t a liquid, it’s a gas. Because gasses flow more freely than liquids, the columns (tubes) need to be longer to achieve the separation of components – they might be dozens of metres long. Gas Chromatography is also used widely in chemistry.

Thin-layer chromatography is another technique, and it’s like an advanced version of the paper chromatography. It’s used for detecting pesticides or insecticides in food.

All of these methods work by separating out the individual components or parts of mixtures and solutions.

Do try this at home…

Chromatography with sweets

More investigations with water and colour

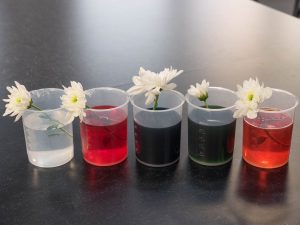

Plants take up water and nutrients from the soil, and this experiment gives you a glimpse of what’s going on. You could use celery instead of flowers, but remember to leave the leaves on!

Transpiration is where water travels from the soil, up tubes in plant stems to all parts of the plant, and eventually evaporates from the leaves. That constant flow of water gives the plant a way of moving food around itself, including moving nutrients from the soil, through the roots, up the stem, to the rest of the plant.

If food colouring is added to the water in the soil it travels up the stem and into the leaves and – with a flower – the petals. This illustrates how nutrients are delivered to all parts of the plant.

In a way, the food colouring you’ve added to the soil is a pollutant – the sort of substance environmental scientists might investigate. It’s not a particularly harmful material, but other pollutants might be. What would happen to the plant if a harmful pollutant was released into the soil?