A-Level Physics Required Practicals:

Measuring the EMF and Internal Resistance of a Cell

All the new specifications include “measure the internal resistance of a cell” as one of the practicals. This is probably a new bit of physics for your students, and although the practical is straightforward to set up, collecting and processing the data is more of a challenge. Comparing two different types of cell, as shown in this film, can make the practical more interesting, with potential for differentiation by ability.

What’s in the Film

The film starts (to 1:24) with the theory which you’ll probably introduce to students before carrying out the practical.

From 1:30 onwards, the film illustrates how you might go about conducting the practical with conventional cells, and also with a button cell (watch battery).

Safety

Christina and Alom do several things in the film to limit the current so the cell doesn’t overheat: they use a limiting resistor, start with low currents, and connect the circuit only momentarily. This represents safe working practice, but heating the cell would also affect the resistance we’re trying to measure.

AA Cell

We used a 10 Ω resistor to limit the current in the circuit. A simple fixed resistor would do, but make sure it can handle the maximum power you expect in the circuit – a few Watts. We didn’t have such a resistor to hand for filming, hence the huge switchable resistance box.

To vary the current to get multiple readings we used an old rheostat, rated at about 16 Ω. In practice anything with a range up to 50 Ω or so should work. It’s also possible to use a range of different fixed resistors, or a switchable resistance box.

Digital or analogue voltmeters or ammeters could be used instead of multimeters, but as Christina points out in the film, the use of multimeters is a skill your students will need to develop anyway. Students will need to select the most appropriate range, which is likely to be 20 V DC for the voltmeter and 200 mA DC for the ammeter (taking care to convert back to amps when processing the data).

Alom’s multimeter films may be dull, but they’ve had a third of a million views so… they may have some redeeming merit. Click through to YouTube or to maximise the film from these tiny windows:

Measuring Voltage with a Multimeter

Measuring Current with a Multimeter

Collecting & Processing Data

Working in pairs, this experiment can be be done very quickly. Systematic data are nice, but as long as there’s a good spread of data points across the whole range of currents, students should get a good result.

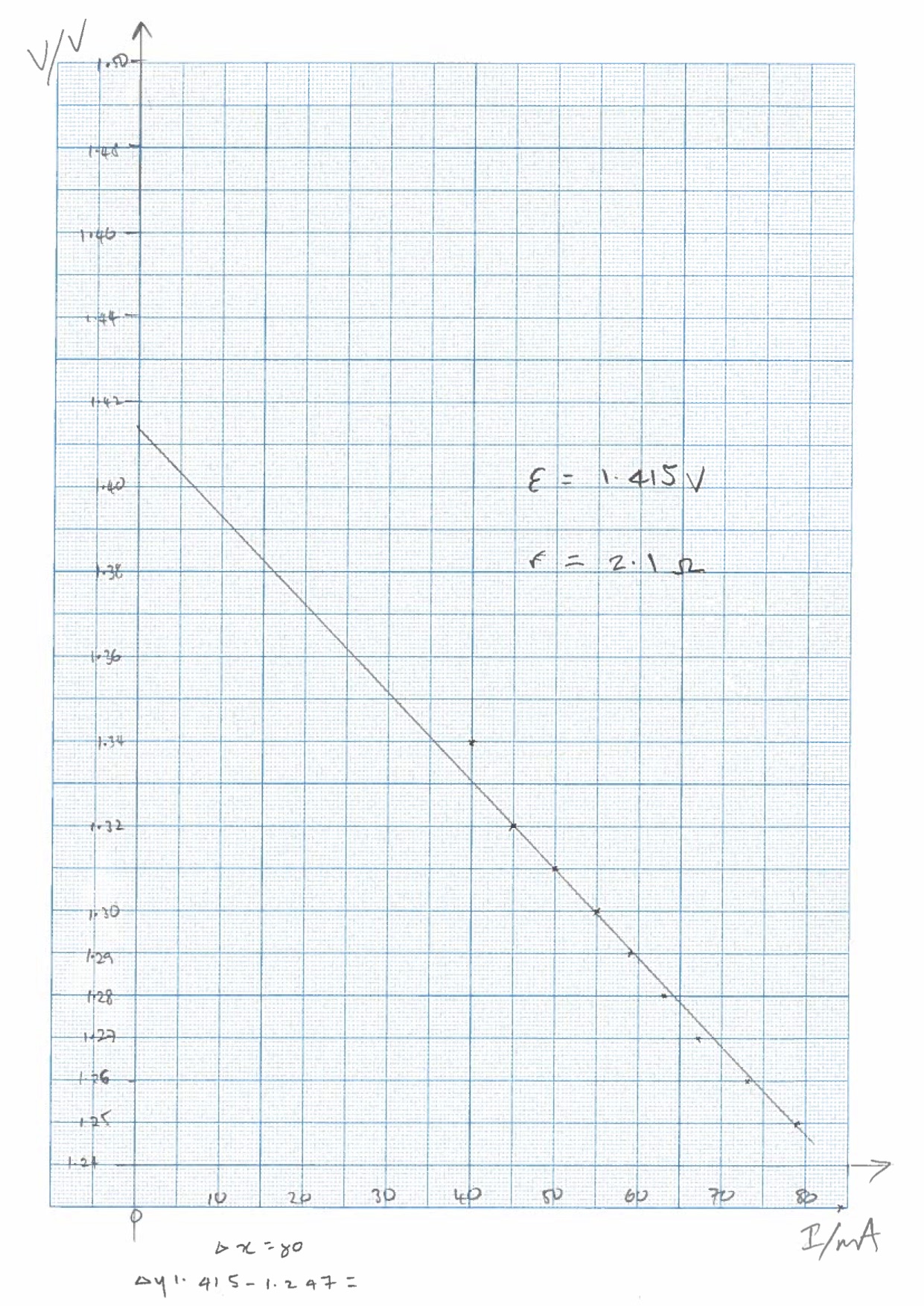

From our data, we arrived at:

Gradient = -2.10

y-intercept = 1.415

so:

EMF = 1.415 V

Internal resistance = 2.10 Ω

We would normally expect an AA cell to have an EMF of about 1.5 V and an internal resistance of about 1 Ω. Ours was old and cheap, which probably explains our results: it’s worth noting that poorer-quality cells can make for a more interesting experiment!

You might ask your students:

- Is their result what they would expect from the cell packaging or label?

- How could they assess the uncertainty in their data?

Christina mentions tolerance at 4’11”, which is a concept with which students may not be familiar. All components have a stated manufacturer’s tolerance, which notes the ±% range which might be expected when the component is in normal use.

Coin Cell

We used a standard CR2032 watch battery. The readings for this sort of cell vary much more wildly than for an AA cell. We’d assumed this is due to internal heating of the cell, but in writing these notes we’ve started to wonder if it’s more about the chemistry that’s going on inside – if there’s a limit to the reaction rate, that would explain why the voltage drops away rapidly (particularly with high current drain cases), before the cell recovers after ‘resting.’ Comments welcome, and for now we’ll move on…

Taking photos of the meters is one way of dealing with rapidly-changing readings. Another approach would be to use analogue meters, which can be easier to read by eye.

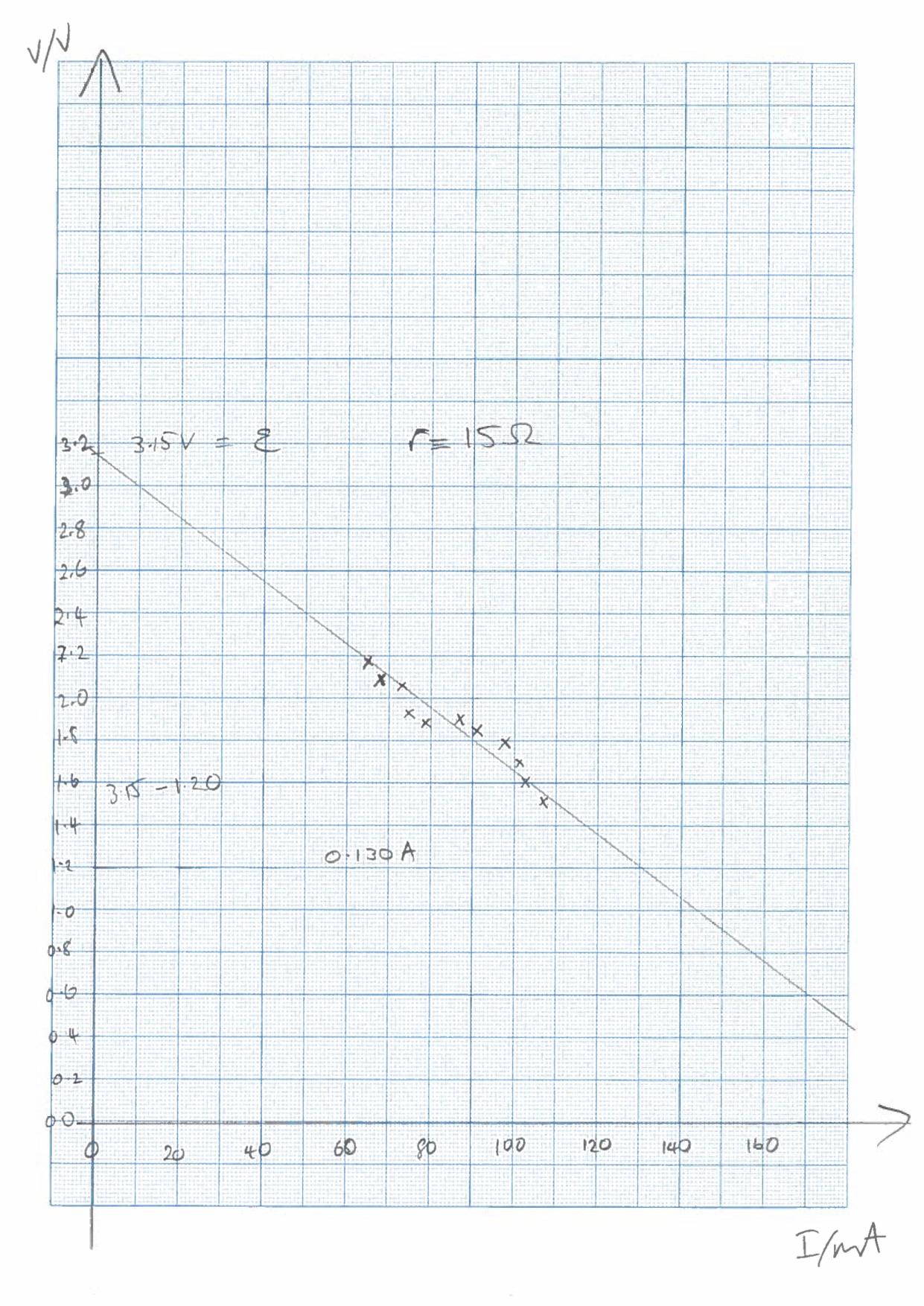

At 6’09” you’ll see Christina using a ‘best fit’ ruler – a clear ruler with a slot through the middle. We recommend these! Our results:

With the increased uncertainty in the readings, Alom suggests repeating the whole experiment twice. Each repeat could be plotted onto the same axes and the gradients and y-intercepts compared. Students could then find the mean EMF and internal resistance, together with their associated uncertainties.

We would normally expect a 3 V cell to have an EMF of about 3 V, and an internal resistance which is much higher than the AA cell – which indeed is what we found, measuring an internal resistance of 15 Ω.

You might ask your students:

- Is there a better way to record the fluctuating readings?

- Is a simple mean a legitimate way to combine repeat readings?

- What’s the best way to deal with data which looked bunched-up on a graph because you need to include the y-intercept? (You could investigate mathematical extrapolation methods here.)

- Why do cells have different EMFs and internal resistance? What chemicals do they contain and how are they structured inside? (a useful resource here is Battery University, though it gets a little… detailed, shall we say?)

Other Notes

Costs

- 50 AA cells should cost about £12.

- 40 3 V coin cells should cost about £5.

Further Work

Some teachers like to challenge their students further by investigating the EMF and internal resistance of a cell made with copper and zinc electrodes and an item of fruit or a vegetable, for example: a ‘potato battery.’ Further guidance on this can be found at the Practical Physics website. Cutting the potato into different shapes can make for an interesting comparison.

Assessment

Common Practical Assessment Criteria

At the time of writing, the exam boards appear to agree that this practical might be used to address, in whole or in part:

- CPAC 1: Follows written procedures

- Correctly follows instructions to carry out the experimental techniques or procedures

- CPAC 4: Makes and records observations.

- Makes accurate observations relevant to the experimental or investigative procedure.

- Obtains accurate, precise and sufficient data for experimental and investigative procedures and records this methodically using appropriate units and conventions.

You can likely prioritise other CPACs should you so choose. There are some more notes on this in the draft student worksheet, below.

Student Worksheet

We’ve drafted a student worksheet for this practical, which you may find useful as a starting point:

- EMF and internal resistance worksheet (Word .docx).

Comments & Feedback

As ever, no single film can encompass everything one might wish to say about a practical. Please, leave comments with your thoughts about the approach we’ve taken, and your suggestions for alternatives or improvements.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Hello there, why do we not need to decrease the resistance of the rheostat in equal intervals? Thank you:)

If you are plotting a graph anticipating a straight line of best fit (LOBF) then having set intervals is not absolutely necessary as you are averaging the relationship by drawing a LOBF. Ideally of course you would still have a good scatter of data points along the LOBF in order to draw a good one so best practice is to leave your equipment set up until you have plotted the graph to see if you need to take some more measurements to “fill in the gaps”

Like to see the table of the graph

OMG we gotz the exact sAMES vaaluess!!!111… wow